Printmaking, Women and the Haptic - exploring the connections between printmaking, touch and women artists.

1. Introduction

2. Women Artists

2.1 feminism and art history

2.8 the gender gap

2.11 collaboration and collectivism

3. Touch and the Haptic

3.1 the haptic and materiality

3.4 the power of touch

3.8 women and touch

4. Printmaking

4.1 characteristics of printmaking

4.8 female-coding

5. Conclusion

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. This paper sets out to consider what are the characteristics of printmaking that appeal to women artists and to what extent the elements of touch and the haptic are important for women printmakers.

1.2. Touch and the haptic have featured in discussions of artistic practice since before Edmund Husserl posited the concept of phenomenology in the early 20th Century. In particular, the haptic, the optical or visual sense of touch, has become an increasingly significant consideration, not only in instances where physical contact with a work is not possible, but especially in relation to discussions of digital art or the increasingly online world we are experiencing.

1.3. Printmaking is a physical experience – from the smell of the acid, the texture of the paper, turning the press and even inking and wiping, it is a full-body activity that engages all the senses. It is also apparent that printing studios are often set up by and for men – equipment is heavy, gloves, goggles and masks are large, drying racks are high up and so on. In common with most artforms, the majority of the most well-known print-maker artists are male, though printmaking as a medium seems to have an appeal for women artists if numbers of women printmakers are an indicator. As well as physical capability and manual acuity, touch, the haptic and sensitivity to materiality are also key in printmaking: the surface of the paper, the plate’s emboss, the quality of the ink are all essential components as integral to the printed work as the image itself.

1.4. Women artists have historically been confronted by prejudice and bias in a variety of forms. Even at its most benign, this often unconscious bias situates the female or some essence of ‘womanness’ at the heart of women artist’s work, reflecting women’s secondary position in the sex hierarchy and their ‘otherness’ in a society that sees male as the default. Physical differences between men and women, including average size and strength, have consequences for women in a world designed by and for men. And these consequences are often problematised as ours – due to our ‘stars, our hormones, our menstrual cycles or our empty internal spaces’ (Nochlin, 2021, p30) – rather than the result of a culture that sees male as normal, active while female is seen as passive and messily aberrant.

2. WOMEN ARTISTS

Feminism & Art History

2.1. With the advent of Western second wave feminism, women began to examine societal infrastructure in order to deconstruct the systems that perpetuate the sex hierarchy. Linda Nochlin’s pivotal analysis of the art world revealed assumptions about genius and worth which were predicated upon the privileges and access that male artists had always enjoyed. It also demonstrated the challenges that women artists faced when ‘(...) everything that happens to us from the moment we enter this world full of meaningful symbols, signs and signals’ hinders them (Nochlin, 2021, p30). The concept of creative genius, which she described as springing forth from the mind(s of men) effortlessly and almost without intentionality stands at odds with our understanding of the effort involved in acquiring skill (Gladwell, 2008) and, of course, in what we know about how great paintings and sculptures were produced.

2.2. Other art historians began to excavate the achievements of women artists that have been hidden by societal disapproval or lack of interest and to interrogate the nature of art history and criticism in relation to women artists, because ‘History is a story told in words as well as deeds: if the accomplishments of creative women aren’t acknowledged, they may as well have never existed.’ (Higgie, 2019, p12). In particular, the rigid moral and social values of Victorian society influenced critical analysis of women’s engagement with the art world. Although there is evidence for these assumptions throughout history, the Victorians promoted and embedded the idea that women artists had particular sensibilities, related to their sex rather than to their socialisation; that they were naturally interested in subjects that reflected the domestic sphere and the inherent ‘tenderness’ of their character and enthusiasms (Parker & Pollock, 1981, p10). Art by women was described in terms of gentleness, delicacy and beauty; and art that was otherwise was attributed to either the artist’s ‘de-sexing’ or their copying of the approach, style and subjects of male artists. Discussing the critical reception Helen Frankenthaler, for example, received, Bett Schumacher writes

‘(...) contemporary critics, whether praising or disparaging Frankenthaler’s abstract canvases, always found them ‘appropriate’. Whether lyrical, delicate, erotic or hysterical, the painting was always clearly a woman’s handiwork’ (Schumacher, 2010, p1)

2.3. Frankenthaler is a key figure in the Abstract Expressionist movement. She developed her innovative ‘soak-stain’ technique for applying paint to raw canvas, which allowed her to create vivid, luminous works that were the among the first examples of what came to be known as Colour Field painting. But femaleness was often referenced in relation to her work – a fact that Frankenthaler found irrelevant and deliberately avoided even at the height of second wave feminism (Pollock, 2012), with the result that she was seen as ‘Too woman for men, insufficiently woman for women’ (Tissier-Debordes & Visconti, 2019). Frankenthaler’s work was often interpreted by critics specifically as separate from but beholden to her male contemporaries – with painter Morris Louis describing her work as a ‘bridge between Pollock and what was possible’; while some even attributed her success ‘solely (...) to her privilege and art-world connections’ (Kirk Hanley, 2012). Even now, her work is determinedly positioned in relation to her male contemporaries – such as a description of Cape Orange (1964) in this year’s Gagosian exhibition as ‘like a Rothko dancing wildly to jazz’ (Jones, 2021) - or as particularly ‘feminine’, with an emphasis on her pieces’ beauty, the colours she used, softness and fluidity.

detail from Orange Hem, Helen Frankenthaler, 1971

2.4. In the 1970s she moved into printmaking, introducing a painterly aesthetic to what might be seen as a more rigid medium. Figure 2 was shown alongside some if its 65 proof versions at the Dulwich Picture Gallery’s Radical Beauty exhibition, demonstrating the lengths Frankenthaler went to and the effort involved in achieving the free, painterly, ‘born at once’ effect in her printed work. She also eschewed the practice of editioning, so that, apart from the various proofs which demonstrate the evolution of a work, each of her pieces is unique – harking back to the tradition of authenticity and exclusivity of her own painting tradition.

Essence Mulberry, Helen Frankenthaler, 1977

2.5. In common with many artists in other media, Frankenthaler worked with master printers, to realise her vision. This collaborative process puts the creative ingenuity alongside the technical skill and understanding of what might be possible and, in the best collaborations – such as Frankenthaler’s with Kenneth Tyler and Yasuyuki Shibata – innovation in both technical and creative fields is the result. Atelier 17, run by Stanley William Hayter, exemplified the notion that collaboration, and the exchange of ideas and skills that it necessarily encapsulates, is the driver for creative innovation (Tallman 2012). Atelier 17’s sojourn in New York during and after the Second World War saw scores of significant American artists experiment in printmaking. Propaganda around the war effort also encouraged women to step into more physically demanding and traditionally male jobs and activities; this was reflected in a number of women printmakers practising at Atelier 17, who were confronted by the physical realities of the print workshop: ‘(...)women printmakers found themselves at the centre of the cultural fray over defining appropriate, feminine levels of physical exertion. Their activities at Atelier 17 challenged the norms defining women’s supportive and less vigorous labour roles.’ (Weyl, 2019, p84).

2.6. Women artists like Louise Nevelson, Louise Bourgeois and Ruth Leaf - who went on to found her own print studio after her experiences with Hayter – developed their own innovative solutions to the problems that arose due to their sex: Nevelson began to use a can opener for her engraving work, finding the physical strength needed to carve metal sometimes too much for her; Louise Bourgeois developed an approach to acid-etching which enabled her to safely etch at home, with her children around her. But innovations such as these were used by critics to reinforce notions of domesticity or femininity as a defining aspect of the work of women artists:

‘Despite the fact that male and female artists often practiced etching and engraving with identical instruments, materials and approaches, critics routinely divided their technical achievements along gender lines. The sharp engravers burin was a weapon when handled by a man, but a dangerous liability for a woman. Textural elements, which appeared regularly in soft ground etchings by both men and women, quickly assumed associations with women’s innate femininity and traditional handcrafts, while being neutral or positive features of men’s prints’ (Weyl, 2019, p91-2)

2.7. This focus on ‘women’s art as biologically determined or as an extension of their domestic and refining role in society’ (Parker and Pollock, 1981, p9) points to a historical need for women artists to be more determined, unconventional and rebellious than their male counterparts to achieve recognition and success (Nochlin, 2021, p68). In looking at the way the art world worked and highlighting its treatment of women, Nochlin and her peers were identifying the structural sexism that hindered women in their efforts to achieve equality with their male counterparts and to live full, interesting lives on their own terms.

The Gender Gap

2.8. This wave of feminism provoked animated discussion and consciousness-raising in Western society in the 70s and 80s; and some headway was made in re-shaping institutions to respond to the specific needs of women that the movement identified and towards women’s equality. It also coincided with other political movements that advocated for social justice around race, disability, poverty and sexuality for example - and analysis of the impacts on different communities of the way that these oppressions intersect - with each other and with sex (Crenshaw, 1989). By the turn of the century though, feminist art historian Griselda Pollock believed she was witnessing the institutional abandonment of feminism as an area of political exploration or value, in art history specifically, but also more widely. She wrote that ‘(...) it seems, those teaching and advising in universities no longer knew of, or recognised, feminism.’ (Pollock 2016, p114) and noted that the last Women’s Studies undergraduate programme closed in 2007. Perhaps it was felt that the work of that kind of feminist critical analysis of art and the art world had done its job and that the structural and institutional barriers to women’s success in art had been removed.

2.9. Certainly, it is the case that female students account for 63% of enrolments on creative arts and design courses in 2019 (HESA, 2021) in England and Wales - although even in 1949, it had been observed that ‘Women fill the art schools, men do the painting’ (de Kooning, 1971) - and that women artists get more exposure and earn greater recognition than previously. However, a survey carried out by the East London branch of the Fawcett Society in 2013 found that women artists accounted for only 31% of both the artists represented by 134 commercial galleries in London and the solo shows held by 29 non-commercial galleries; that in Westminster and City of London only 8% the 386 public art works were by women; and only a quarter of the artists selected for the 4th plinth in Trafalgar Square were female (East London Fawcett, 2013). These disparities are echoed in the annual Freelands Foundation report Representation of Female Artists in Britain, with the additional information that women artists are likely to earn more than £4,000 per year less than the UK minimum wage; and that the gender ratio for Arts and Design staff in UK universities is worsening, with an increasing gap between the pay of male and female top earners. In addition, fine art and other creative subjects face the threat of reduced funding for and access to education from a government which implicitly ties the value of education to sectoral earning potential. A 50% reduction in subsidies for creative higher education courses will be introduced in 2022 (Fazackerley, 2021) and there have been suggestions of proposals to reduce the numbers of students for these courses too.

Collaboration & Collectivism

2.10. Feminist activism, from the British women’s suffrage movement onwards, has used collectivism and collaboration as a means to effecting positive change in policies and institutions, but also a mechanism for mutual support and inspiration: ‘for years women have intuitively collaborated in small communities of women’s groups as a survival strategy for maintaining a life of the mind and for allowing respite from a patriarchal culture that has diminished, ignored, or excluded their unique contributions’ (Ellerby and Waxman, 1997, p207). Collaborations can see complementary skills and ideas brought together for the mutual benefit of participants and the production of a product, message or work of art which has wider appeal and impact, as the result of the broader range of inputs to its development.

2.11. Printmaking is a collaborative medium: artists often work with master printers to deliver their vision; the scale and nature of equipment needed means that most printmakers must work in a shared workshop, with access to presses, stones and screens, an acid room, drying space and so on. This collaborative, supportive aspect of the medium could be key for women artists as they ‘wrestle with inner demons of self-doubt and guilt and outer monsters of ridicule or patronising encouragement, neither of which have any specific connection with the quality of the artwork as such.’ (Nochlin, 2021, p80). Operating within a context established by and for men can be a dispiriting and exhausting activity, even with the support and encouragement of male peers and teachers. This might be one reason behind the founding of women’s printmaking collectives like the Tamarind, Universal Limited Art Editions, and See Red Women’s Workshop; and collaboration as a key component of printmaking sits neatly alongside printmaking’s function as tool for disseminating ideas. Barbara Jones-Hogu, for example, was a founder member of AfriCOBRA, a collective of Black artists based in Chicago that sought to foster self-confidence and solidarity among African Americans. Jones-Hogu and her peers celebrated Black culture, style and attitude, encouraging recognition of the contribution of Black people to American society and countering racist narratives, through the use of a collective aesthetic that drew on the practices of all its members (Jones-Hogu, 2013).

2.12. Other women-led collectives were not so much motivated by social justice or progressive ideals but did have as a guiding principle widening awareness of printmaking as a creative medium. The Tamarind Lithography Workshop was founded by June Wayne in 1960 with the express intentions of restoring the prestige of lithography as a print medium in the US and of habituating its member artists to responsive and stimulating collaboration, with a focus on research and innovation (Tamarind History, no date) Tatyana Goldman established Universal Limited Art Editions as a means of supporting her family after her husband’s heart attack; Helen Frankenthaler was among the first artists to work with ULAE and a close relationship developed between such print studios and some of the most significant artists in the Abstract Expressionist movement.

2.13. This movement began to understand the canvas as an integral part of the painting, not just a surface for paint or even a window through which to view the painting’s object. Inspired by this perspective – and despite the differences in their beginnings - both Tamarind and ULAE began to reflect on the print as a whole object: not just an artefact of reproduction, but a work of art in which the materiality of each of its component parts – paper, ink, matrix – was essential (Adams, 1997). The importance of materiality in printmaking reflects the physicality of the process, it ‘(...) implies a shift from the optical to the haptic, from a purely visual regime to the centrality of the physical act of transferring a trace by direct contact.’ (Roca, 2018, p101). Not only this but, as Frankenthaler’s prints demonstrate, the constituent materials in printmaking - the seductive tactility of ink and oil, the texture of the paper, the embossing by plate, block or stone – and the way that their physical qualities are interpreted and understood, mean that touch and the haptic are important components of the printmaker’s work.

3. TOUCH & THE HAPTIC

The Haptic and Materiality

3.1. Printmaking is a physical, labour-intensive medium, a full body experience that engages all the senses. But a sensitivity to materiality and the haptic is evident in the work of printmakers and their passion for it as an art-form: ‘You might also be sensitive to the insistent flatness that remains, even if your print takes on three-dimensional aspects. And although the tactility of print media may be something only a practitioner is aware of, or someone who actually handles prints, it does exist.’ (Balfour, 2018, p125).

3.2. Barbara Walker’s Vanishing Point series look at the representation of black people in Old Master art. Taking eleven works in the National Gallery, she produced photo-etched blind-embossed reproductions of each, before drawing in the black figures as they appear in the original. Because Walker mimics the scale of the original work, the result is a large expanse of white paper with only a small, often peripheral and solitary, figure of a black person in it; its effect highlights the way in which black people have been portrayed within the fine art canon as marginal, servile and exotic (Walls, 2020, p2).

Diana and Actaeon, Titian, 1556-9

3.3. The blind emboss in this reinterpretation of Titian’s Diana and Actaeon (1556-9) renders the faces of the non-black figures as blank and expressionless, lending them an almost indolent, uninterested air; the viewer’s focus on the woman brought to vivid and detailed life by Walker’s drawing, in contrast to other figures’ lack of awareness and care. The juxtaposition of blankness and detail serves to separate the drawn figure from the others, creating a sense of separation and space that is almost physically tangible. In this work, and in contrast with the norms Titian experienced, the white people are othered and become background decoration or wallpaper (think of anaglypta or lincrusta) while the black woman is given life and agency. ‘Various forms of print media, from those with aspects of incision, deep biting and low relief on one end, to the more smooth and planographic on the other, allow for a range of the haptic as well as visually perceptible phenomena (...)’ (Balfour, 2018, p125) and in Walker’s series, the relief created by the blind emboss conveys the sense of the 3D nature of the work and the materiality of the paper surface; contrasting with the visual complexity of the drawing. Walker’s use of printmaking for this series recognises the medium’s historical development as a means of reproducing painted or drawn works of art (Alston, 2018, p1), but also demonstrates the importance of touch and the haptic within printmaking.

Vanishing Point 7 (Titian), Barbara Walker, 2018

The Power of Touch

3.4. Touch is fundamental to the healthy development of human children. Researchers have found that lack of human contact was a factor in the impaired growth and cognitive development as well as heightened incidence of serious infection and attachment disorders among infants housed in bleak eastern European orphanages (Ardiel and Rankin, 2010). The importance of touch in the growth and development of infants across species is recognised, for example, in the habit of some mammalian mothers of licking their new-borns, in grooming behaviours among primates and other animals, even in microscopic roundworms. This importance to growth and development of touch might be behind notions of touch as the more ‘feminine’ of the senses, related to women’s traditional role in the nurturing of babies and raising of children.

3.5. Evidence supports the power of touch in managing illness, with greater levels of immune cells to combat the virus in HIV patients undergoing daily massage, as well as improvements in response to treatment from burn patients to sufferers of eating disorder where massage therapy is introduced (Ardiel and Rankin, 2010). Royalty was deemed to confer the divine gift of healing, exercised by the laying on of hands in what was known as the ‘royal touch’ (Croizat-Glazer, 2021); an idea that was echoed in the visit by the Princess of Wales’ to the first dedicated hospital ward in the UK for patients with HIV and AIDs, where she shook the hand of a man living with HIV (Gold, 2017). Diana’s overt and public rejection of fears around physical contact with AIDS sufferers heralded a shift in public attitudes towards and acceptance of people with HIV and demonstrates the societal significance that touch can have. There is also a cultural relationship between women and touch - it is doubtful the Prince of Wales shaking the patient’s hand would have had the same resonance - in both benign and malign ways. This is evident not only in suggestions that a mother’s hand on the forehead is more effective than a thermometer in identifying fever in children (Teng et al, 2008), but also in the accusations against women accused of witchcraft - touching people and animals to induce sickness or fits were among claims made, for example, and touching was even among the common tests to establish guilt as a witch (Linder, 2009).

3.6. The link between manual capacity and neurological development is key in humans, as a species and as individuals. The fine motor skills that develop throughout childhood enable us to explore and understand the world even before we can speak, and to express ourselves before we can write. Henri Focillon posited touch as our most importance sense and primary means for engaging with things ‘...before they have been trapped by language. We touch things and grasp their essence before we are able to speak about them.” (Focillon, 2018, p.36). He saw our manual ability as the key to the development of knowledge, suggesting that it is an essential element of being able to describe - and so understand - the basic and important characteristics of our world. In fact, our brains have been altered by our manual acuity: ‘There is growing evidence that Homo sapiens acquired in its new hand not simply the mechanical capacity of refined manipulative and tool-using skills but (...) an impetus to the redesign, or reallocation, of the brain’s circuitry.’ (Wilson, 1998, p.59). The very infrastructure of our brains has been shaped by our ability to engage with, understand and adapt to our environments through the sense of touch.

3.7. From this fundamental link between our sense of touch and our neurological development, we can see that the copying and repetition of actions to learn and develop a skill – physical mimesis and embodiment in learning - are as important as perception via our other senses: ‘(...)the transference of the skill from the muscles of the teacher directly to the muscles of the apprentice through the act of sensory perception and bodily mimesis (…) the task is lived rather than understood.’ (Pallasmaa, 2009, p.15). This is the basis of muscle memory, the almost unthinking deployment of physical action, which frees up our consciousness for more focused thinking, the generation of ideas and problem solving.

Women and Touch

3.8. Researchers have explored sex-based differences in use of touch as a form of communication, but it is difficult to disentangle gender expectations and masculine/feminine stereotypes from the analysis of the results and sometimes even from the framing of the research questions. Early research in this area found that men were more likely to initiate touch than women (Henley, 1973) and postulated that those who had power and status were more willing to use touch than those without. Later research found that touch was more likely to be initiated by men, but continued by women – and that overall, there was no asymmetry between the sexes (Hall and Veccia, 1990). More recent research has attempted to analyse differences between the sexes in using touch to communicate emotion between pairs of volunteers. Interestingly, this research found that anger could only be communicated between a pair that included a man, that sympathy could only be communicated between a pair that included a woman and that happiness could only be communicated between a female-only pair (Marsh, 2010). That said, while the methodology had each pair attempting to communicate from behind a screen with only one arm reaching through a hole to touch the other person, the person being touched was able to accurately identify the sex of the person touching them at least 70% of the time (and up to 96%), suggesting that socialisation and unconscious bias could easily have had an impact on results (Hertenstein and Keltner, 2006).

3.9. There is evidence that women tend to have a more heightened sense of touch: a review of nerve receptors in the cheek skin of cadavers found, on average, almost double the number in female samples than in men (DeNoon, 2005). An analysis of tactile acuity – the ability to interpret the spatial structure of surfaces pressed on the skin – found consistent differences between the sexes, with women able to perceive finer detail through touch than men. However, researchers concluded this was down to finger size, with smaller fingertips having a greater density of Merkel receptors (the nerve endings in the skin which facilitate tactile perception); in men with smaller fingertips, tactile acuity is on a par with women (Peters et al, 2009).

4. PRINTMAKING

Characteristics of Printmaking

4.1. In printing of the most basic kind, we use our fingers or hands to leave imprints on other surfaces. We might do this unintentionally - leaving prints or traces of ourselves wherever our fingers or lips, for example, might land. But parietal art more than 30,000 years old found in the Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc cave in south-eastern France includes a series of red dots near the cave entrance that have been deduced to be a series of palm prints made by two different individuals (Baffier and Feruglio, 1998). This is the first evidence yet uncovered of intentional printmaking: using hands to transfer an impression to another surface to create an image.

4.2. As our first prints are made with fingers, palms, even feet, so we progress to potato-prints and rubber stamps as small children. Using these tools, we continue to explore ‘...the irreducible essence of printmaking ...[as] an embrace, one body pressed against another’ (Weissberg, 2018, p63), but begin to introduce an intermediary between ourselves and the artefact we create, in the form of the matrix - ‘...an apt word to describe the models or forms from which images are pulled or produced, particularly when ‘plate’, ‘block’, or ‘stone’ can’t describe the proliferation of current technological possibilities.’ (Reeves, 2018, p75). The matrix is the material printmakers use to produce an image through its impression onto a different surface and can be almost anything – parts of the body, found objects, etched copper plates, carved limestone – that is capable of making an impression.

‘The material form from which the matrix is made is negligible, as long as the structure permits making an impression.... neither materiality, or the type of shape, nor how it was made or if it was made at all have an effect on whether a matrix is a matrix.’ (Bednarczyk, 2018, p86-87)

4.3. Bednarczyk is setting out the ground rules here for identifying a matrix, and at the same time describing the defining characteristic of printmaking: transferring a trace from one surface to another. He also explains that the matrix is not a tool for producing an image, it is something more intrinsic: ‘What distinguishes it from a tool is the final content inscribed in it and the passive giving of the content to the original. A tool on the other hand, although its structure affects the product is beyond the content and active by its nature.” (Bednarczyk, 2018, p87). A tool is used actively by the artist to affect the final image, where a matrix transfers and translates the image to create the print.

4.4. As a fine art discipline, printmaking developed alongside the evolution of the written word. Early printed media incorporated imagery to reinforce and increase the impact of the writing, but also to communicate ideas to those who could not read. Printmaking’s capacity for reproducing images and ideas – but also, importantly, preserving them - meant that artists began to explore its intrinsic values. This includes the democratisation of ideas and culture and the expansion of audiences, through production of multiple copies of an image - which allows for many more people to see, discuss and understand the image and the artist’s intentions: ‘Prints provide a mirror, reflecting the artist’s engagement with technology, however simple or complex, to produce multiple images that enter culture and circulate…crossing boundaries, states and time.’ (Coldwell, 2010, p5).

4.5. Printmaking has been an effective tool for artists to communicate their message urgently and widely - the term propaganda having been coined in 1622 by the Catholic Church as means for propagating faith (Kunzle, 2011). From Käthe Kollwitz decrying poverty and war in early 20th century Europe to the London-based collective See Red Women’s Workshop producing feminist posters in the 70s and 80s, the graphic and reproductive nature of print has enabled the rapid dissemination of ideas. Kollwitz documented the lives and miseries of working-class people, fascinated as a child by their ‘speed and movement, the strength and grace of their bodies’ in contrast to her own dull, middle-class life (Egremont, 2017, p15). She was commissioned to produce a series of seven intaglio prints depicting the German Peasants’ War, a popular uprising inspired by the protestant reformation in 1525 of which Battlefield is the sixth (Carey, 2017, p112).

Battlefield, Käthe Kollwitz, 1907

4.6. She deployed many different intaglio techniques to achieve this dark, atmospheric print, which shows Black Anna, a prominent figure in the uprising, searching among the dead for her son. Kollwitz uses the light of the lantern to bring an intimacy to Black Anna’s terrible discovery of her dead son, the sea of corpses within which she finds him alluded to by the snarl of deeply etched, black lines that evoke bodies stretching into the distance behind her. The horror of Black Anna’s task – and her realisation of the consequences of her own incitement to violence – are evident in the darkness of the image, with the faces of Black Anna and her dead son brought into sharp focus: this is a powerful and moving image, which conveys the awful consequences of war.

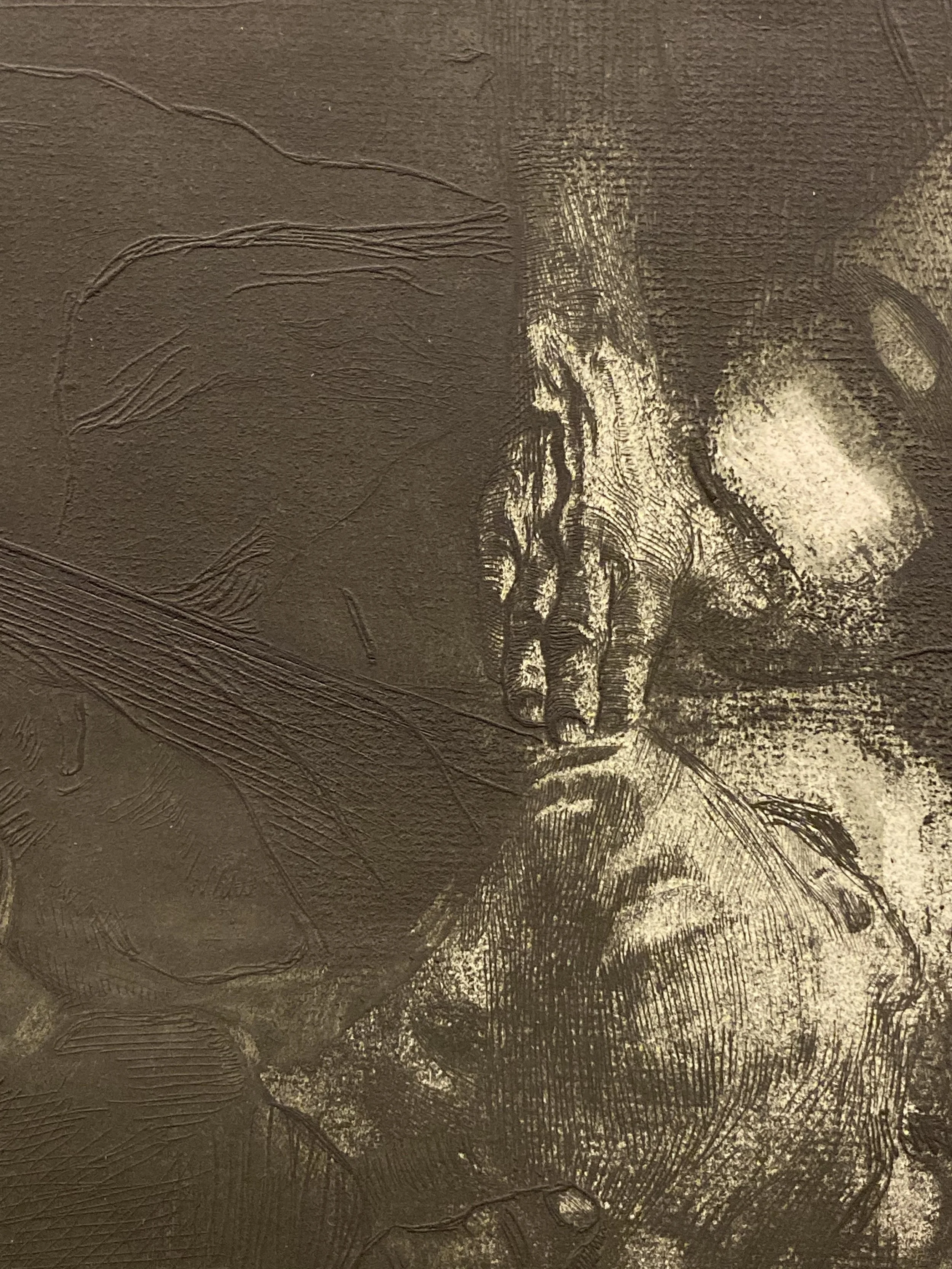

4.7. While compelling in itself, a close look at a detail of the print also offers evidence of the printmaker’s skill and the processes used in the preparation of the matrix: the sharpness and depth of the etched lines is evident in the visible height of the ridges of ink on the paper surface; the textures made by pressing into soft ground; and the varying tones, including the deepest black, that indicate the use of aquatint. This is an eighth state print (each revision of the plate by an additional process takes it into a new state) and Kollwitz used a series of processes to achieve it: lines drawn in drypoint and etched with acid; variations in tone introduced with aquatint, texture introduced with sandpaper and impressions of different kinds of paper made in soft ground prior to etching. This plate would have taken weeks, if not months, to prepare.

detail from Battlefield, Käthe Kollwitz, 1907

4.8. The repeated revision of the matrix, to fine tune the intended final image, is an aspect of printmaking that some consider essential to its nature: decision-making, consequences - whether intended or not – and fixing issues arising are key aspects of the medium’s appeal for some printmakers. ‘This is our delight and our challenge. The final image is the visible consequences of all one’s decisions.’ (Weisberg, 2018, p63). Barbara Balfour describes needing ‘... the mental alertness that enables one to detect a problem arising at the proofing stage – inevitably leading to the need for trouble-shooting – and the flexibility to change one’s direction and work with the unexpected, arising through engagement with process.’ (Balfour, 2018, p124). But she also recognises an apparent dichotomy between the effort that goes into producing a print, and the print itself:

‘All of this inescapably physical activity tends to result in a surprisingly thin layer of ink on a sheet of pristine paper, often with no apparent signs of the labour involved. I have often likened this and other curious print processes that demand repeated effort to that of housework, in which success ultimately lies in the lack of evidence of any mess or work involved.’ (Balfour, 2018, p125)

Female-coding

4.9. Balfour is not alone in making a connection between what is traditionally women’s work, or the female, and aspects of printmaking. The word ‘matrix’ is the Latin for ‘womb’ – a direct link to the female and the capacity for reproduction: ‘Embedded within the production of prints and print-based works will always be the notion of (...) the matrix ‘mother’. (Harding, 2018, p111). Printmaking is often described as ‘labour-intensive’ because of the nature of the repeated revisions of the matrix that are often involved; and it can be physically demanding - heavy presses, large lithographic stones and continuously moving between sites in the studio such as the sink, press and drying rack. So while ‘...the matrilineage of matrix resonates and the link between matrix, reproduction and printing is unmistakable’ (Reeves, 2018, p75), there are other aspects of it that can be maintained to support the notion of printmaking as a female-coded activity.

4.10. It has been argued that printmaking has a secondary status within the world of fine art, partly because of its function in producing copies - for preservation or wider dissemination - of works created in other media, partly because printmakers provide a service to other artists: the creative input being the artist’s, while the printmaker solves the technical problems of how to achieve their vision. That printmaking is often perceived as less valued in the art hierarchy is said to be another factor in its ‘feminisation’, because as women move into a workforce, that industry becomes perceived as less valuable, interesting, important. This is evident in changing attitudes towards - and numbers of men and women in the workforce of - computer programming, which was initially treated as secretarial, mechanistic and low-skilled. Now it is male-dominated and openly misogynistic industry – that also prizes the heroic genius valorised in art - making it a hostile environment for women workers (Criado-Perez, 2019, p104). So the perceived secondary status in a world which is male-dominated would point to female-coding for printmaking – second class, subservient, lacking in creative genius. Katherine Reeves considers this perspective and concludes:

‘The gendered code of printmaking explains much in relation to issues of marginalisation, reproduction and originality. If print images spring from a matrix/womb, they are ordinary mortals. The genius, who is never gendered female, produces something different (...) Creation is constructed thus, and not as reproduction; it occurs without labour and without the matrix/womb.’ (Reeves, 2018 p76)

4.11. The practice of editioning might also contribute to a sense of printmaking as less than other media. The value of editions is that while a number of versions of the work exist, there is no ‘original’ of which the others are copies; each of the editions is the artwork, but they have an equivalent authenticity which arguably diminishes their value compared to a unique piece. This is known as a type-token relation, which might be used to describe artforms where each musical performance, production of a play, showing of a film is an instance of the artwork.

‘Because multiply instantiable art forms have no single object that can be pointed to as the artwork, the ontological questions multiply in kind. We wonder what, exactly, constitutes the artwork, and how we can determine which instances count as successful iterations of the work.’ (Grover, 2018, p163).

In an edition of 10 prints, it is not possible to define only one as the original, authentic artwork; the matrix is not the artwork, though it is the site of the creative labour; nor is the BAT (bon à tirer, meaning ‘good to pull’) which only serves an administrative function to indicate the artist’s approval to the printmaker for the edition.

4.12. Ruth Pelzer-Montada suggests that it is, in part, the inducting of printmaking into the fine art pantheon which might have reinforced this idea of a secondary status, that applying the academic, art historical perspective to printmaking as a medium is what has revealed its gender-coded nature: ‘Viewing print through the lens of critical theories (...) also yield[s] a convincing explanation of print’s marginal status as a feminine-coded practice in a patriarchal or masculine-coded, hierarchical art world.’ (Pelzer-Montada, 2018, p52). The purpose of critical theories is to expose assumptions and this instance provides an interesting and novel perspective, but the value in this particular interpretation might be limited and is arguably driven by, as well as furthering or embedding, perceptions of female as necessarily meaning secondary and lesser. The practice of ‘coding’ activities as male or female offers thought-provoking analysis and highlights assumptions that we all make, often at a subconscious level – unconscious and implicit bias (ACAS, no date). But it might also lead us to misconceptions about how to elevate either printmaking as a medium within the fine art canon or the activities of women working in print. Reeves goes on to say ‘Attempt[ing] to reconstruct printmaking as masculine in order to reposition its rank in the art world is to accept patriarchy, hierarchy and opposition as the natural order of things.’ (Reeves, 2018, p77). If printmaking has a secondary status, it is because of its relative infancy as a medium and issues around reproduction and multiples - in contrast with traditional media such as sculpture or oil painting, where the authentic and unique are valued. But this could also be a strength: ‘Increasingly, however, print-making’s ‘ex-centricity’ and its outsider status are regarded as a vantage point rather than a disadvantage.’ (Pelzer-Montada, 2018, p3). Printmaking’s status as non-elite reinforces and supports its original function as a mechanism for democratising education, ideas and art.

5. CONCLUSION

5.1. Women do tend to have greater tactile acuity than men, but this seems to be down to average size – women’s smaller fingertips have a greater density of receptors. It is difficult to separate this tendency from assumptions and stereotyping based on gender, even in scientific studies that attempt to remove even unconscious bias. Any essentialising of touch as a female strength or characteristic is much more likely to be rooted in women’s traditional roles in nurturing and caregiving. So, it cannot follow that women have a particular affinity for a medium so centred on materiality and touch because of some physiological capability, but it is possible that there are aspects of printmaking that do appeal to women.

5.2. Given what has been revealed through feminist analysis of societal and institutional bias, it is likely that the collaborative, supportive aspect of printmaking in a studio or workshop is important for some women: the possibility for learning in a supported environment and the potential for innovation through collaboration and experimentation, as well as simply being around other people for company, socialisation and networking, the cross-fertilisation of ideas. It is also possible that the scope for intellectual problem solving and finetuning - in a world where women are often seen as emotional and illogical – might attract some women to printmaking; also, that success in a technical, process-led medium is likely to rely less on the creative ‘genius’ of the artist – an attribute which is rarely applied to women. Perhaps even the slow, considered long-term work required of the most complicated prints are more in line with (and can fit more easily around) other ‘women’s work’ – caregiving, domestic upkeep and child-rearing. Printmaking’s secondary or non-elite status and the characteristics which differentiate it from the more traditional, canonical media, might actually be why women printmakers engage with and fall for the medium.

5.3. It is apparent though, that while women have made significant headway against the men’s primacy in the world of art, equality has by no means been achieved. The UK’s national institutions are taking steps to deliver better representation for women artists, but the Freedland Foundation’s research shows just how far there is to go before any kind of parity is achieved between male and female representation or earnings. While threats to higher education funding for creative subjects will further inequalities in the arts sectors and could ultimately mean that only those who are financially independent can pursue careers in art.