Critical Reflection - January 2023

key themes for research

landscape

intimate immensity

memory

I’m interested in landscape and our connection to it, particularly how aspects of the landscape – its geology, the impacts of human intervention – provide a temporal record of events or interactions and how we as individuals relate to them. My practice involves working from and with photographs of landscape that represent significant moments or people in my life. I work mostly in print, but I’m really interested in the boundary between 2D and 3D and have been exploring that and taking it into some ceramics work also.

I have narrowed my key themes down to three: landscape, intimate immensity, memory. But geology, temporality and materiality are important too, so I am trying to weave these themes into my writing here.

Iandscape

Landscape, intimate immensity and memory are intrinsically linked for me and my current practice, which is based around particular moments within particular landscapes, sometimes with particular people. These might be what Virginia Woolf described as ‘moments of being’ – when we step outside of the day to day and feel at one with the world around us – or memories of people that are strongly connected in my mind with particular places (Woolf, 2002). So I am thinking about how it feels to be in the landscape; what my psychological state was at the time; how I remember it – bearing in mind the fragility and unreliability of memory; and also a sense of duality in these experiences: my personal feelings set against universal concepts of life and death for example; or the scale of the landscape that I am in alongside the tiny details of plant or animal life; the patterns in the stone underfoot set against the eons over which it was formed.

Catrin Webster’s lecture at the start of term introduced me to cultural geographer John Wylie, who discusses whether landscape is ‘the world we are living in, or a scene we are looking at, from afar?’ (Wylie, 2007) and goes on to examine what he sees as a series of tensions – between body and mind, proximity and distance, immersion and detachment. I find this approach interesting, because my fascination with landscape is around the totality of the experience – the body is physically engaged in navigating the landscape even as the mind is engaged with its sights, sounds and emotions; as one is observing a scenic view, one is also inhabiting it. The challenge here is how to capture both the scale and detail of the experience of being in a particular landscape, and how to convey them simultaneously, through art, to others; and, for me, to do this and to convey a sense of landscape in a manner that is not the traditional, beautiful view. This is my object partly because my attempts to capture ‘the view’ don’t do justice to its aesthetic impact; but also, because some of the moments in the landscape that have most resonance with me are not classically beautiful. How to capture and convey the essence of a cold, grey New Year’s Day on the south coast when the tide is out and the wind fiercely driving in?

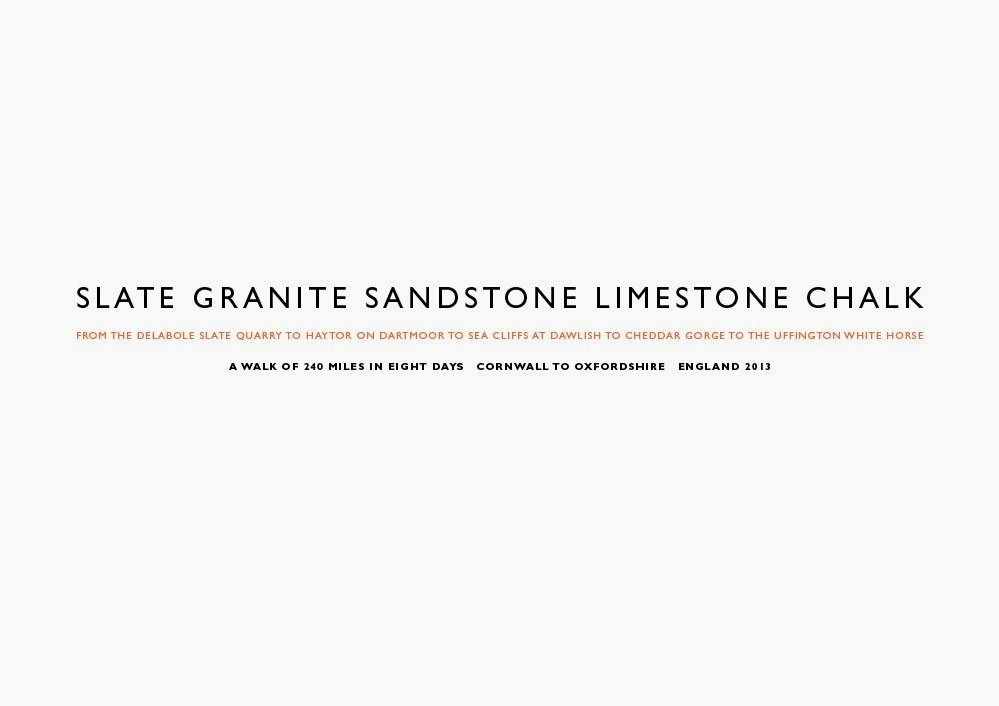

Slate Granite Sandstone Limestone Chalk 2014, Richard Long

I looked at Land Art and the work of artist Richard Long, who describes ‘a state of grace when I’m on a wilderness walk on my own, with just my rucksack on my back and my camping food. I’m mentally free from the stuff of modern life. It’s a romantic idea, but it is powerful. It’s nice to be able to touch that psychological state once in a while’ (Cole, 2016). His series of text works capture ‘the rich experience of a walk’ in the simplest of forms, almost as if the reality of experience is too powerful to express. This piece, for example, describes a walk over 8 days - that took him from Cornwall to Oxfordshire - in just 40 words. In focusing on the journey, Long defies the traditional notion of landscape as a scenic view and simultaneously distils more than a week’s experience into the barest of facts. Chinese landscape art emphasises the Tao or Way, focusing on the artist’s journey towards becoming one with nature. Long is inseparable from his journey in this piece and so from the landscape. He evokes the varied topography and geology of the particular landscapes that he passed through which are available to all of us, but it is very specifically his experience over those 8 days in 2013.

Part of my response to this question of how to capture my experience of being in a landscape has been to photograph separate elements that constitute landscape –the striations in rock, a portrait of a tree, the detail of sea worn wood found on a beach – and use those images as the basis for exploring different print processes. This approach also stems from a sense of dissatisfaction with my more traditional landscape photographs, which can’t capture the scale, sense of space and vibrancy of the real thing; and results in an impulse to focus on the small, intimate, over-looked in my images; what is under foot as much as what is all around; the hidden or unseen.

Black Path (Bunhill Fields) 2013, Cornelia Parker black painted bronze 340x250x9cm

Cornelia Parker, talking of her piece Black Path (Bunhill Fields) calls it a ‘worm’s eye view’ (Parker & Schlieker, 2022). She cast the cracks between the flagstones on the route she took, passing William Blake’s grave, each day walking her daughter to school. So this seemingly simple idea encompasses all the richness and intimacy of this key part of her daily routine as well as William Blake’s legacy and the physicality of a large public space. Parker also elevates the over-looked or discarded in her work: her ‘Negatives’ series showcases the remnants and discards of other activities: the residue accumulated from engraving words in silver or from cutting the grooves into vinyl records – literally tiny pieces of detritus that allude to profound human concepts of language and sound.

Intimate Immensity

In Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space, he discusses the dualities of scale and how small or intimate things intrinsically connect us to the immense or universal. I often think about the way that aspects of birth, life and death are so profound on an individual, personal level and simultaneously so universal that, on a global scale, they are almost mundane for their ordinariness and the frequency with which they occur. Perhaps the focus on the miniature or intimate is a way to contain or manage concepts or emotions which might otherwise be overwhelming in their scale; to address their vastness or significance in a more manageable way.

Untitled (Ocean) 1975 Vija Celmins, graphite and paper, 31.7x42cm

Vija Celmins achieves a sense of intimate immensity in her ocean series, narrowing the field of vision to focus on the minutiae of the surface of choppy sea, for example, while simultaneously evoking a vast and constantly moving ocean that is intrinsically linked to global systems of tide and weather. In her galaxy pieces, she captures the personal perspective of the night sky on a clear night, while also reminding us of the immensity of space and the insignificance of our place in the universe.

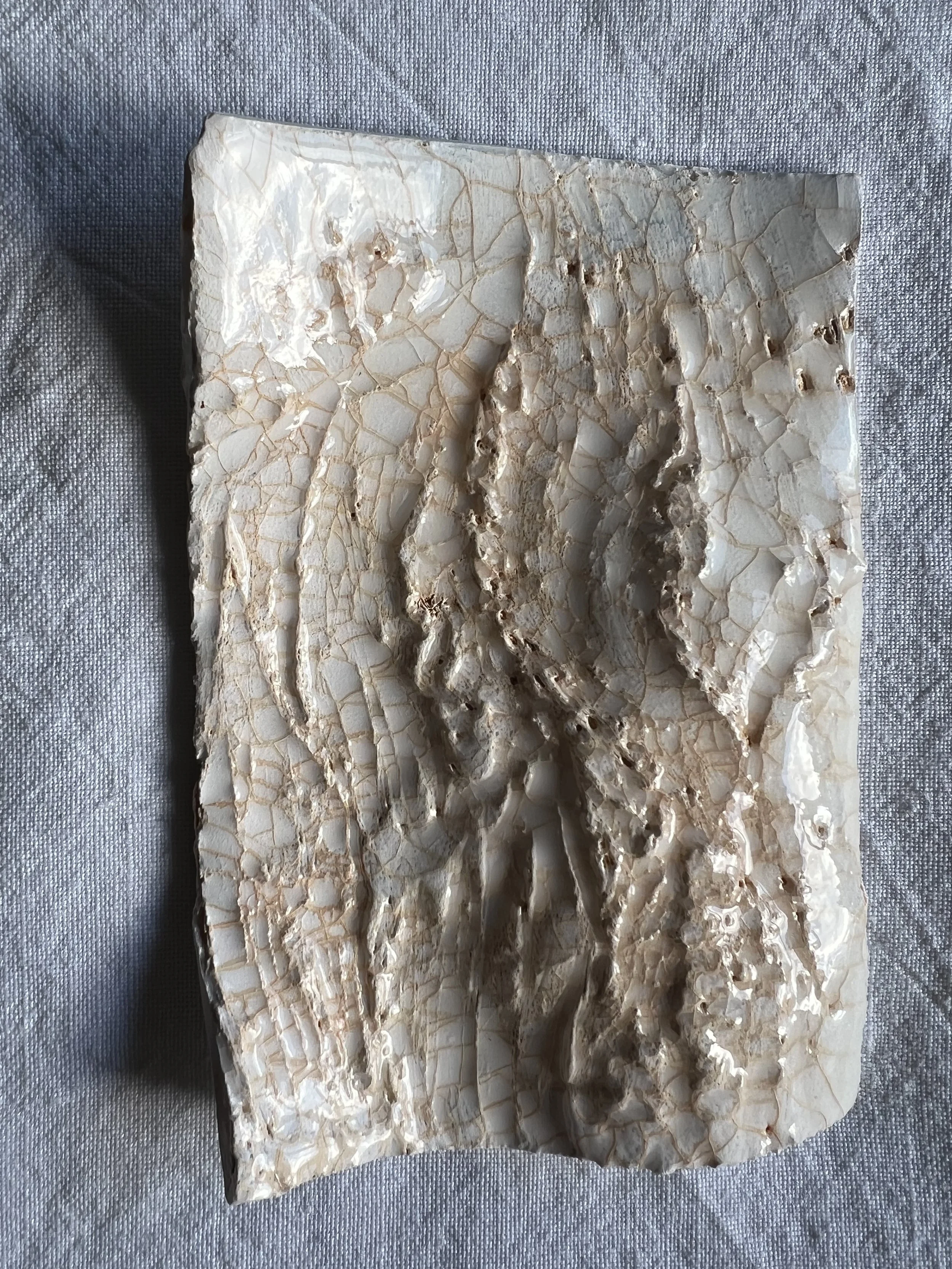

In working with clay, I’m using material that is literally earth – part of what forms the landscape - even when working with the refined and delicate porcelain. I took impressions from wood blocks that have been laser etched with photographic images of rock, which were then fired and, in some cases, glazed. I think the results can be read as representing a small fragment of something larger but at the same time, in the undulations of the forms and the tiny ridges and valleys in the surface of the porcelain, also an entire landscape. This captures that sense of duality, of an object that suggests simultaneously miniature and vast, or a sensation that is intimate and personal but also immense and universal.

untitled, 2022

glazed porcelain with ink 135x90x3mm

Memory

One of the things that fascinates me most about landscape is the way it is formed: its geology is a history of all the events that made it; and there is a record too of the human interventions that shape our world. Sometimes these interventions are overlooked or half-forgotten, such as the clearing of high-forested land in the north of England during the iron age which resulted in the fells we know today, or the reclaiming by nature of German farmland whose population was decimated by the Black Death which is now the Black Forest (Flyn, 2021). But the evidence of those events – and of the melting of glaciers or the disappearance of inland seas – is retained within the landscape itself. If landscape is a record or archive of all the events that have shaped it, whether human or natural, so, indeed, are we; and as we – as individuals and as a species – are affecting landscape, then surely we are affected by that landscape in return.

Artist, academic and writer Charlie Lee-Potter is interested in how landscape might leave its trace on us, beyond the psychological traces of experience and memory. She adopted the term fotminne – remembering with your feet – from Kerstin Ekman’s 1993 novel Blackwater to examine how the visual arts can “measure or record …the visceral effect that landscape has upon us” (Lee-Potter, 2020). The temporal element of recollection – memory only occurs once the relevant event is in the past – is akin to the archival quality of the landscape: our personal record of our experience within and of a landscape which differs even from that of people we may have shared specific sites and moments with.

Fotminne, 2020, Charlie Lee Potter

300 pieces of hand-moulded porcelain, 1,200 cm. (4 x 2 cm each)

My exploration of landscape and memory led me to think about how sites reflect our values, emotions, perceptions back at us. Places that we visit with other people will give rise to difference perceptions and experiences, even if we’re there at the same moment. Artist and Academic Tracy Hill’s 2018 project Haeccaeity explored the way in which we make connections to and develop memories of landscape; and how memory and movement influence our perceptions of landscape. Haecceity is defined as that property or quality of a thing by virtue of which it is unique or describable as ‘this (one)’, a concept developed by mediaeval philosopher John Duns Scotus to describe separate realities of the same ‘thing’. I think of it as the difference between ‘this chair’ and ‘a chair’. Haecceity is a quality that is relevant not only to a place, but also to our experience of that place at a given moment. This is what I’m seeking to explore in my own practice – how the ‘this one’-ness of a place combines with my psychological state at the time, but also with my own, potentially unreliable or fragmentary, memory of that moment.

Temporal Wandering, 2015, Tracy Hill

intaglio-type etching, dimensions not known

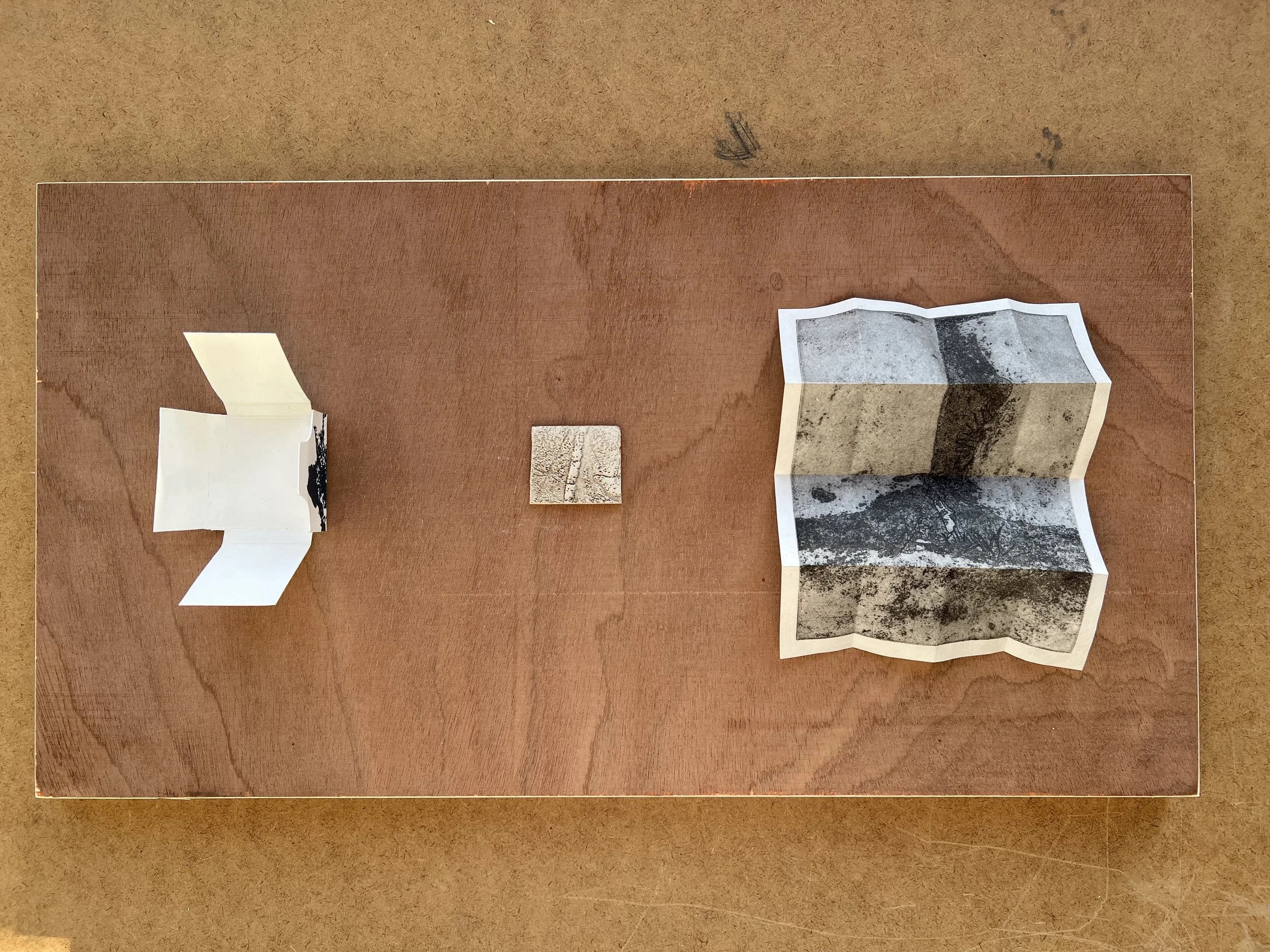

My pieces for the pop up were the first, more considered iteration, of this idea. I wanted to create a sense of intimacy, of containing memories and personal connections, protecting them and holding them close - even carrying them physically with you; but also, to evoke something larger and universally salient, in the allusion to absence and loss, as well as the scale of the places that the pieces were inspired by and the temporality inherent in them. So the tiny phase box unfolds to reveal a fragment of clay – symbolising the kind of memento that you might pick up on a walk, a shell or pebble – with some paper which also unfolds to reveal the image of ferns in the deep gulley between three rocks, from a photograph taken at Malham Cove; on the back is a map of the circular walk from Malham, around the Cove and Goredale Scar. It’s the last walk I did with my dad before he died in 2021 and I wanted to give a sense of something huge – the loss, but also the landscape – being contained within something tiny; a way of preserving my memory of the place and of him, but that might also speak to something more universal.

Last Walk with Dad, 2022

screen-printed phase box (3x4cm closed), clay fragment (2.5x3.5cm) , photo transfer intaglio print on Awagami hosho paper (11x15cm)

Going Forward

Using images of limestone and slate, I had been developing an interpretation of landscape through looking down rather than looking out or across and was starting to integrate that with ideas around memory. I want to dig deeper into these ideas and see how I can take them further in my practice, particularly in relation to dualities of scale. I feel that the connection to landscape and sites of psychological significance, via the notion of what is literally under our feet, allows a lot of room for exploration.

This first unit I have been learning new processes and developing my skill in others and much of it has been based around a straightforward production of images. I’m not sure this is the right direction for what comes next, though I do want to think about ways to use different print processes together – integrating etching and lithography, for example, or screen-print and etching, perhaps in relation to the idea of landscape as archive or palimpsest – and in creating 3D pieces too. Scale will obviously be important in what I do next, not only in terms of being more ambitious, but also in exploring the ideas around intimate immensity and the miniature vs vastness.

The haptic continues to be an area of interest for me, not only in relation to the materiality of the resources I use in my work, but also in the embodied experience of being in the landscape, how that relates to how memory is embedded and the traces of time spent in the landscape – both in terms of what we take with us and what we leave behind.

bibliography

Bachelard, G., Jolas, M., Danielewski, M.Z. and Kearney, R. (2014) The Poetics of Space. East Rutherford, UNITED STATES: Penguin Publishing Group.

Balfour, B. (1998) not_ necessarily.

Clark, T.A., Finlay, A. and Shone, O. (2000) Distance & proximity. Edinburgh: Pocketbooks, Morning Star, Polygon.

Cole, I. (2016) 'Ideas Can Last Forever', Sculpture, 35(6), pp. 20-27.

Dean, T. (2018) Tacita Dean: landscape, portrait, still life. London: Royal Academy of Arts.

Dubuffet, J. (1966) Jean Dubuffet: paintings ; a retrospective exhibition organized by the Arts Council of Great Britain at the Tate Gallery, London 23 April-30 May. London: Arts Council.

Flyn, C. (2021) Islands of abandonment: nature rebounding in the post-human landscape. New York: Viking.

Holt, N., Lee, P.M. and Williams, A.J. (2010) Nancy Holt: sightlines. Berkeley, Calif., London: University of California Press.

Lailach, M. and Grosenick, U. (2007) Land art. Köln: Taschen.

Lee-Potter, C. (2020) Fotminne: How Might Visual Art Represent Landscape's Imprint Upon Us?.

Lefebvre, H., Elden, S. and Moore, G. (2013) Rhythmanalysis: space, time, and everyday life. London, England: Bloomsbury.

Long, R. (1981) Twelve works 1979-1981. London]: Anthony d'Offay Gallery].

Merriman, P. and Webster, C. (2009) 'Travel projects: landscape, art, movement', Cultural geographies, 16(4), pp. 525-535. doi: 10.1177/1474474009340120.

Moore, A. (2015) 'The Anthropocene', Environment and society, 6(1), pp. 1-3. doi: 10.3167/ares.2015.060101.

Parker, C. and Schlieker, A. (2022) Cornelia Parker. London, England: Tate Publishing.

Ruskin, J. (2006) Lectures on LandscapeDelivered at Oxford in Lent Term, 1871.

Schaaf, R., Worrall-Hood, J. and Jones, O. (2017) 'Geography and art', Cultural geographies, 24(2), pp. 319-327. doi: 10.1177/1474474016673068.

Shepherd, N. (2011) The living mountain. Edinburgh, Scotland: Canongate Books.

Turner, M. (2009) 'Classical Chinese Landscape Painting and the Aesthetic Appreciation of Nature', The Journal of aesthetic education, 43(1), pp. 106-121. doi: 10.2307/40263708.

Wong, W. (1991) The Tao of Chinese landscape painting: principles & methods. New York: Design Press.

Woolf, V. (2002) Moments of being: autobiographical writings. London: Pimlico.

Wylie, J. (2007) Landscape. London, New York: Routledge.