Magdalena Abakanowicz – Every Tangle of Thread and Rope (2022) [Exhibition], Tate Modern, London 17th November 2022 - 21st May 2023

I often think of printmaking as being a whole-body experience – the physicality of working the press, the smell of the inks, solvents and acid, the feel of the paper and so on – and when I think about my experiences in the landscape, the encounters with places and the memories I am trying to preserve, they are physical as well as visual: the way my eyes were narrowed due to the brightness of the sun, the tiredness in my legs, the sounds and smells as well as the sights surrounding me. Tate Modern’s exhibition was also a whole-body experience and it prompted me to think about ways that I could encourage or induce a more holistic engagement on the part of the viewer. Abakanwicz’s textile pieces have an obvious haptic quality - a sense of tactility that is visual, in the absence of touch being allowed - but they have a smell too and their scale, as well as their group installation at Tate Modern, are physically dominating although not in an intimidating way. They seem to invite touch and exploration, though clearly it is not possible to do either in a gallery setting - so there is a frustration in the staging of her ‘Abakans’: a playfulness and tactility about them that invites touch, but in a formal gallery setting – and observed by staff – where we know it isn’t allowed. There is a question for me about how I can invite people to engage with my work – look closer, touch it, open boxes – in a subtle way and in the face of a cultural practice that says art is for looking at, not touching.

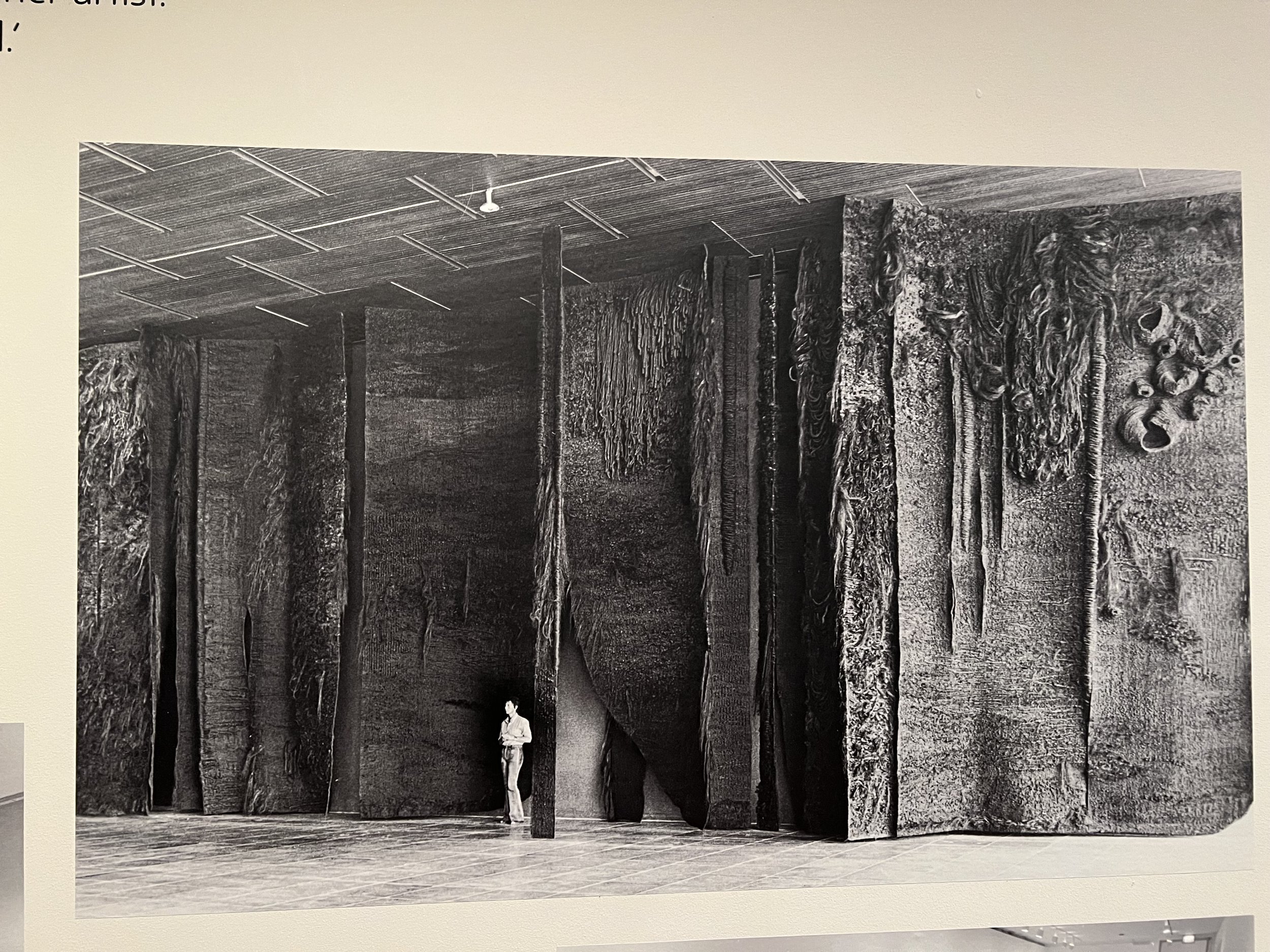

photograph of Artist in Front of Bois le Duc, Provinciehuis van Noord Brabant, ‘s-Hertogenbosch, the Netherlands. ©Abakanowicz Arts and Culture Charitabel Foundation. Photographer: Jan Nordahl (1972) (own image)

detail of Black Garment VI (1976) (own image)

The Attraction of Print: Notes on the Surface of the (Art) Print – Ruth Pelzer-Montada

Pelzer-Montada’s essay considers printmaking’s relationship to contemporary painting, photography and digital media through the surface of the art print, but I found interesting its discussion of haptic visuality. According to critic Laura U Marks, cited by Pelzer-Montada in the essay, “Haptic visuality… draws from other forms of sense experience, primarily touch and kinesthetics.” – it is a visual sense of touch, which Pelzer-Montada relates to the tactile surface of a print made with traditional technologies, that involves rich layers of ink on a high quality, heavyweight paper surface. This sense of tactility is something that I value in my own practice – and is part of the reason why I want to push my printmaking more into 3D - to emphasise the tactile quality of the surface and its image – and why so many of the images I use are textural and somewhat ambiguous. While the photographic images I use are personally significant, there’s a flatness to them that feels unsatisfying. In my practice, printmaking translates a digital image through an analogue, even atavistic, process, which I think adds meaning and weight to the source image. So Pelzer-Montada’s discussion of surface – and particularly the description of viscerality versus enervation in relation to surface and screen respectively – helped me understand some of what has been driving my practice but I have struggled to articulate. In particular, the idea of embodied seeing that underpins the notion of haptic visuality seems to chime with the ‘whole body experience’ that I was discussing in the previous context – and is something that I will need to explore in the next unit.

Berthe Morisot – Shaping Impressionism (2023) [Exhibition] Dulwich Picture Gallery, London 31st March – 10th September 2023

I find myself more interested and invested in art by women - in part, I think, because so much of the ‘canon’ is male, that looking at the work of women artists feels like an adventure or journey of discovery - and so I have deliberately sought to focus on women artists in my research. Berthe Morisot was one of a small number of classical women artists who enjoyed recognition during her own lifetime and the current exhibition at DPG looks at her influences, her life and her work, with detailed interpretation and explanation accompanying each picture. In her 1970 essay, Linda Nochlin talked about the necessary conditions in which those few, well known women artists managed to achieve their success – ‘have a good, strong streak of rebellion’ (Nochlin, 1970) and come from a wealthy family that is interested in and supportive of the arts, both of which apply to Morisot. But it was a small insight into how she went about her work that stayed with me: the necessity for starting work early in the morning or siting herself away from others to avoid ‘curious crowds’ – which prompted two thoughts. The first that women have always had to be cognisant when outside of the domestic sphere about how others might perceive them and seek to engage with them – obviously still an issue for any woman that runs, or walks a dog late at night, or wears a sundress… The second thought was that these efforts to avoid interruption add to the workload – unseen and additional tasks that make Morisot’s achievement, despite the advantages of a wealthy family and a rebellious spirit, even more significant.

The Freeland Foundation’s latest annual report into representation of Women Artists in the UK shows that despite women accounting for the 66% of undergraduate art and design students and 55% of Arts Council grants to individual artists, male artists account for 67% of representation by commercial galleries and over 60% of artworks acquired by the Tate collection in 2021 (Bonham Carter, 2022). So, it continues to be harder for women to achieve commercial success in the arts, despite significantly more women studying art and pursuing art as a career.