Documentation

Resolved Works

MA Show

Research & Reflection

Experimentation

My practice has continued to develop around memory and intimate immensity, with landscape and time spent in nature as the lens through which I consider these ideas. As I experiment with different methods, materials and contexts, I have been shifting focus between a number of different concepts that are inter-related:

- tactility and the haptic, how the physical experience of being in the landscape and ideas of embodied perception can be explored through the form and materials used in a piece;

- intimate immensity and ideas around duality – inside/outside and vast/small – that allow for a universal salience to even the most personal memories or emotions and allow us to move between different ways of engaging with the world;

- looking down as a way of discovering the unseen and overlooked; as a means of avoidance or to focus on where we are going; and as the way we engage with or observe closely something that we hold in our hands

- memory and loss, including the compulsion to preserve memories in the face of absence, the fragility and fallibility of memory, and the deleterious effects of time on memory and materials.

Resolved Works

Liminal Immanent (2023) installation view

concertina book made from laser etched woodcut on Awagami hosho paper; porcelain tiles, acrylic paint, paper, relief print and ash burr veneer

51x51x365cm

At the Edge of Vastness (2023)

concertina book made from laser etched woodcut on Awagami hosho paper, with laser etched plywood covers

21x21x432cm

Dialectics of the Skin (2023)

collaboration with Joy Stokes

monoprint on Zerkall paper with porcelain tile and acrylic paint

76x56x10cm

Land and Sea (2023)

collaboration with Aya Kikkawa

digital print on hosho paper with porcelain tiles and watercolour paint

80x220cm

Winder to White Fell (2023)

hard ground etching on Somerset Satin

21x40cm

untitled (2023)

photographic image on porcelain

7x5cm

untitled (2023)

photographic image on porcelain

7x5cm

Fluid Dynamics (2023)

collaboration with Joy Stokes

lithograph and laser-etched woodcut on Zerkall paper

76x56cm

MA Show

Planning

Reflecting on the show in March at Bargehouse, I wanted to work at a larger scale but continue to push the concept of intimate immensity. I felt that the juxtaposition of two quite different pieces that shared the same subject had worked well in terms of reflecting this idea and encouraging a more active engagement with the work on the part of viewers; I had been pleased to see some people crouching down to look more closely at the detail of the image and the emboss in 50° 55' 33”, 0° 45' 56” 08.02.23 and the, often bright, sunlight falling on Resolve to Infinity encouraged people to shield it with their hand and get really close to view the footage.

Thinking about this, I had planned to make a large scale piece out of up to 750 small porcelain tiles, that would represent a personal, emotional landscape; feedback confirmed my concern that perhaps it was too similar to work by other artists, but also suggested that the detail of each individual tile would be lost in the overall piece and that invitation to look more closely might be lost. So I returned to the idea of at least two pieces – again a large scale printed piece and smaller audio-visual work, but this time with sound (which I had felt, on reflection, was an obvious omission from Resolve to Infinity), and potentially some of the porcelain tile pieces, presented individually. For practical reasons, I decided to continue to work with the shoreline image that I had used at Bargehouse (the laser-etched plywood plates took some time to make and limited access to the laser cutter meant I would not have time to make more) and to find a way to scale up the printed outcome and to make more of the sculptural, 3D form; and for the AV piece, I planned a small scale projection into a box, returning to the idea of keeping memories safe, but this time not trying to hide the mechanisms and perhaps suggesting the difficulty inherent in preserving a particular memory and protecting it from distortion or deterioration. I was trying to think about ways of bringing landscape - and the experience of being in it – into the gallery or exhibition space, so was looking at the work of artists like Victoria Ahrens and Victoria Arney, members of the Geographies of Print collective, and the way that they convert sensory and physical experience into something visual - and vice versa. Mariele Neudecker’s tank pieces offer an entire, evocative world on a scale that can be held in one’s arms; and Richard Long’s text-based works describing his walks are a kind of spare, minimal poem to the experience of time and place.

testing for installation

sketch of initial proposal

Resolution

I adopted a concertina book form for my print piece – as a way of achieving a sculptural, interesting form at scale and also as an allusion to the more intimate way we tend to engage with books, holding them in our hands and looking down to read them. Folded, or closed, the book was 51cm square but opened out, it extended to 1.5m by 4.5m. Although I initially envisaged a print piece that went from wall to floor, I decided to show the book at floor level, to echo the experience of standing ankle deep in the sea at the shoreline, but with the geometry of the folds suggesting a livelier sea or a landscape, as well as evoking a map in the process of being unfolded. In the pursuit of a further layer of engagement or meaning - around tactility and the materiality of the print surface - I had used a softly textured hosho paper which was strong enough to hold an emboss within the image. However, the weight of the paper meant that - at this scale - it could not hold any form without mechanical support: unfolded on the floor it simply slid open until it lay completely flat. The solution was to use folded aluminium lithography plates to support the structure – these would be visible under the book form, but their shiny, metallic surface suggested sunlight on the sea.

My intention with the AV piece was to project footage, with audio, of a running brook in Wales into the bottom of a matchbox. The idea was again around putting things into a small box for safekeeping, but this time taking the technical aspects of it outside the box, to be able to focus more on the simplicity of the idea, even if the manner of realising the idea was visible. I cut away the back of a matchbox and lined it with thin white paper to provide a ‘screen’ onto which the footage could be projected; and I built a structure to hold the projector and its cabling and sit it within a plinth, projecting upwards into the bottom of the matchbox.

I picked four porcelain tiles out of the 50 or so I had made by pressing clay into the plywood that I had laser-etched with photographic images. I selected these for having particularly interesting surface or form: one I had been testing with watercolour paints and it had two interesting tide marks on it that suggested land or sea and horizon; two had torn as I removed the clay from the plywood plate; and the fourth had an interesting curve resembling a wave. I was keen to keep these tiles in the body of work that I was presenting to be able demonstrate or share my interests around materiality, surface and the haptic - and the importance of small, pocket-sized or hand-held pieces to my ideas around duality and intimate immensity.

I wanted to show the tiles floating horizontally, to emphasise their delicacy and fragility and also to suggest geological strata. I positioned one on a relief print made with a photograph of rock strata and another on a piece of wood veneer that had multiple burrs, a bit like waves, so referencing the sea and nature more generally. The last two I painted the undersides with fluorescent paint and placed them against a white background which reflected the colour, creating a glowing effect that served to highlight the tiles and heighten the sense of floating. I had sourced some plinths for floral arrangements that were simple white metal frames and allowed for a view right through, as I did not want anything too solid to detract from the porcelain’s sense of lightness and being untethered or free.

In addition, I had asked two classmates to collaborate with me on separate pieces, putting some of my porcelain tiles alongside prints of theirs. My collaboration with Joy Stokes was a bit more formalised and considered further in advance of installation beginning – thinking about surface, the skin, fragility vs strength, and the consequences of Joy’s lymphoedema; whereas Aya Kikkaya and I got together only the week before to devise a piece together that was focused on our shared interests in landscape, nature and memory. In both cases, I felt that my work and theirs worked aesthetically, but I also found their concepts compelling. I saw a direct connection in Aya’s work around landscape and we share some interests in methods and materials; I loved the delicacy of her work and the way that she brings potentially conflicting ideas and contrasting cultures together in it. With Joy, we shared experiences of grief and loss, as well as an interest in materiality and tactility, despite our processes and visual outcomes being quite different. I was moved by her exploration of the impact of her lymphoedema diagnosis; and her reflections on the effect on her skin and the steps she has to take to care for it reflected my own experiences with occasionally chronic eczema. In both collaborations, I felt there was space for my exploration of duality and intimate immensity to support their conceptual interests.

We also learned that there was the opportunity to have a group show, held at the Wilson Road site. For this, I decided to explore the book form at a different scale – smaller, only 25cm square, but stretching to 4.3m when unfolded – and bound with covers made from plywood laser, etched with the source image and stained with ink. This was an opportunity for me to experiment with more pronounced folds, because at this scale the paper held its form much better, and in different modes of presentation. It also conveyed that sense I was looking for of something large being contained within something smaller – and of something complex and intricate being contained within something simpler.

Outcome

During installation, it was evident that showing my printed book on the floor, in what was quite a busy space, would mean that it would feel quite lost. Jo Love suggested we utilise the plinths that I had for the porcelain tiles to suspend the book above the ground, which immediately gave it visual impact, but also achieved the lightness and sense of floating that I was looking for with the porcelain pieces. I added the tiles and their supports at the bottom of the plinths, and this had the effect of creating further layers, echoing both the layers that form the landscape and the layers of experience with which we build memories. At this stage in the installation – the last day – and because I had my own large and complicated installation plus two collaborations, I opted to drop the AV piece.

Despite these last-minute changes, I felt that Liminal Immanent was successful in representing my ideas effectively and holding its own in a busy exhibition space. The scale of the piece overall meant that people had to engage with it in quite a physical way – at least walking around it and perhaps bending or crouching to see the tiles at floor level. The peaks and folds meant that light could play on the different planes, casting interesting shadows and creating highlights that reflected and drew attention to different aspects of the image, surface and form. Its size and the weight of the paper also meant that it struggled to hold its form at times, needing some occasional adjustment to counter the effects of time and gravity. So the piece was also constantly, though perhaps mostly imperceptibly, changing – again reflecting its subject and the temporal aspect to both memory and landscape.

My installation also connected the two collaborative pieces, which then led on to the individual work of both Joy and Aya, even though their practices and the concepts they are exploring are quite different. There was a sense of audience engagement with all the pieces, drawn in by differences in scale, height and colour palette, that gave a sense of flow between the work.

laser-etched plywood plates

the 20 prints that made up 'At the Edge of Vastness'

testing 'At the Edge of Vastness'

testing 'Liminal Immanent'

wood veneer & porcelain tile on a light box

installation of 'Land and Sea'

testing 'Dialectics of the Skin'

installation at floor level

bringing the plinths into effect

installing support for 'Liminal Immanent'

testing porcelain tiles and backgrounds

installation views

installation view of 'Synchronized' show

'At the Edge of Vastness'

private view

Research & Reflection

I wanted to investigate further ideas around scale, transitional or evocative objects and looking down. Walking in the Yorkshire Dales and Switzerland gave me opportunities to photograph aspects of the landscape, to gather objects and record traces of the walks in hard ground on copper plates. I found myself drawn to running water and many of the images that I returned to at the end of the summer with work in mind were those I took of streams and rivers. I see this as a natural progression from my work before the summer around the sea and reflecting some thoughts I had about our connection to water, its different forms – including the glaciers we saw in Switzerland – and the recent conversations about pollution and its impact on river health; and the ubiquity of plastic microparticles in our water.

Again, I find there is an element of duality in my reflections: purity vs pollution; small vs vast; local vs global; intimate vs universal. Additionally, I was thinking more about the difficulties inherent in attempting to capture or contain something as nebulous and shifting as emotions and of efforts at preservation that cannot evade the effects of time and use: degradation, decay and entropy.

Rawthey Weir

Cautley Beck

Cautley Spout

Rawthey River

Tschingelbach

Experimentation

Conscious of the limited time that I would have access to the facilities and technician’s expertise at college, I wanted to get to grips with some processes and methodologies that I had been thinking about for a while. I particularly wanted to explore ways of separating tones in photographic images so that I could start to introduce novel and counter-intuitive colour palettes into my prints – thinking about the viscosity prints that I had made in unit 2 and translating that freedom with colour into other processes. There seemed to be two approaches: digital separation of an image into highlights, mid-tones and shadows and producing a different matrix for each; and exposing images to light for different amounts of time to produce any number of matrices with different levels of information – a more analogue approach.

Analogue separation

- hydro-coat: zinc plate with light-sensitive coating

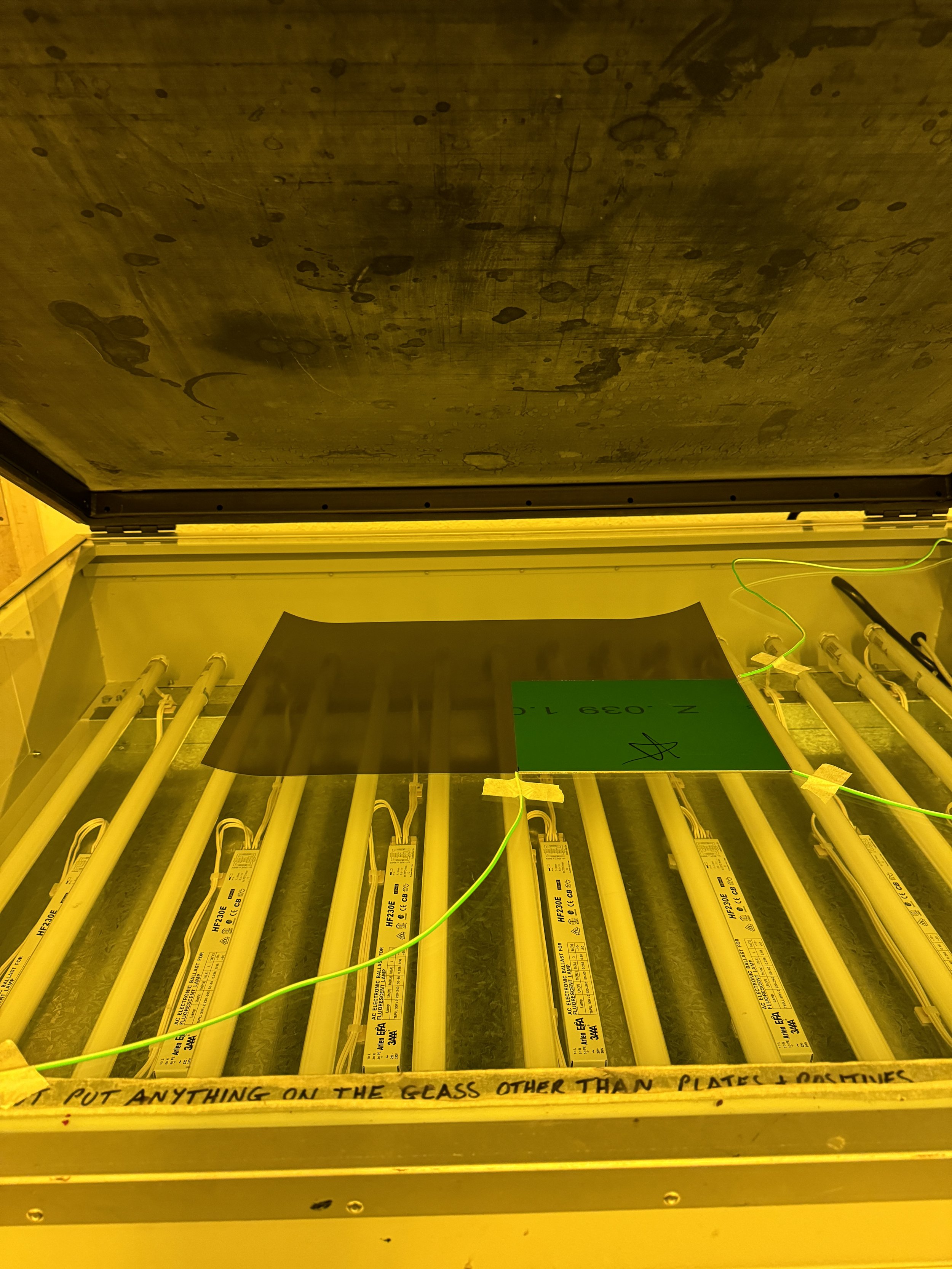

Brian Hodgson was keen to do some experimentation around the aquatint screen and using this approach – common practice pre-Photoshop – to produce plates or screens that could be layered in multiple colours. We decided to do a set of plates without the aquatint screen that we would manually aquatint after etching, to be able to compare. In all we did 8 plates, 5 of which were exposed first to the aquatint screen for 2 minutes 30 seconds and then to the image: times were increased in 1 minute increments from 2 minutes 30 seconds to 6 minutes 30 seconds. These plates were then open bite etched for 1 minute 30 – I felt the blue coating was on the verge of lifting in some places.

We did 3 plates without the aquatint screen that were exposed increasing 1 minute increments from 2 minutes 30 seconds to 4 minutes 30 seconds. The plates were double aquatinted with a 2 minute etch each time, to get a stronger black.

I did not manage many prints with these plates, but multiplate prints using this process are all about the effect of overlaying colours, so it is a very different approach to the digital separation and leads to blended colours and significant areas of white (or whatever colour the print surface is) in the print.

reference image for hydro-coat plates - Cautley Spout

exposure unit set up with aquatint screen and wires to ensure tightest possible vacuum

after washing the exposed plate

plate made without using the aquatint screen

plate made with the aquatint screen

detail from aquatint plate

detail from plate exposed without aquatinit screen

'analogue' aquatinting after exposure using resin

aquatint screen plate exposed to image for 5 mins & 30 seconds

aquatint screen plate exposed to image for 3 mins & 30 seconds

aquatint screen plate exposed to image for 2 mins & 30 seconds

starting the multi-plate print process with magenta

adding yellow with a second plate

a third plate in black reveals that I should have reversed the order and done the first plate, with the least information, in black

printing the plates in the reverse order

plate 2, adding yellow to the mix

using blue for the final plate rather than black

testing different approaches to colour and wiping

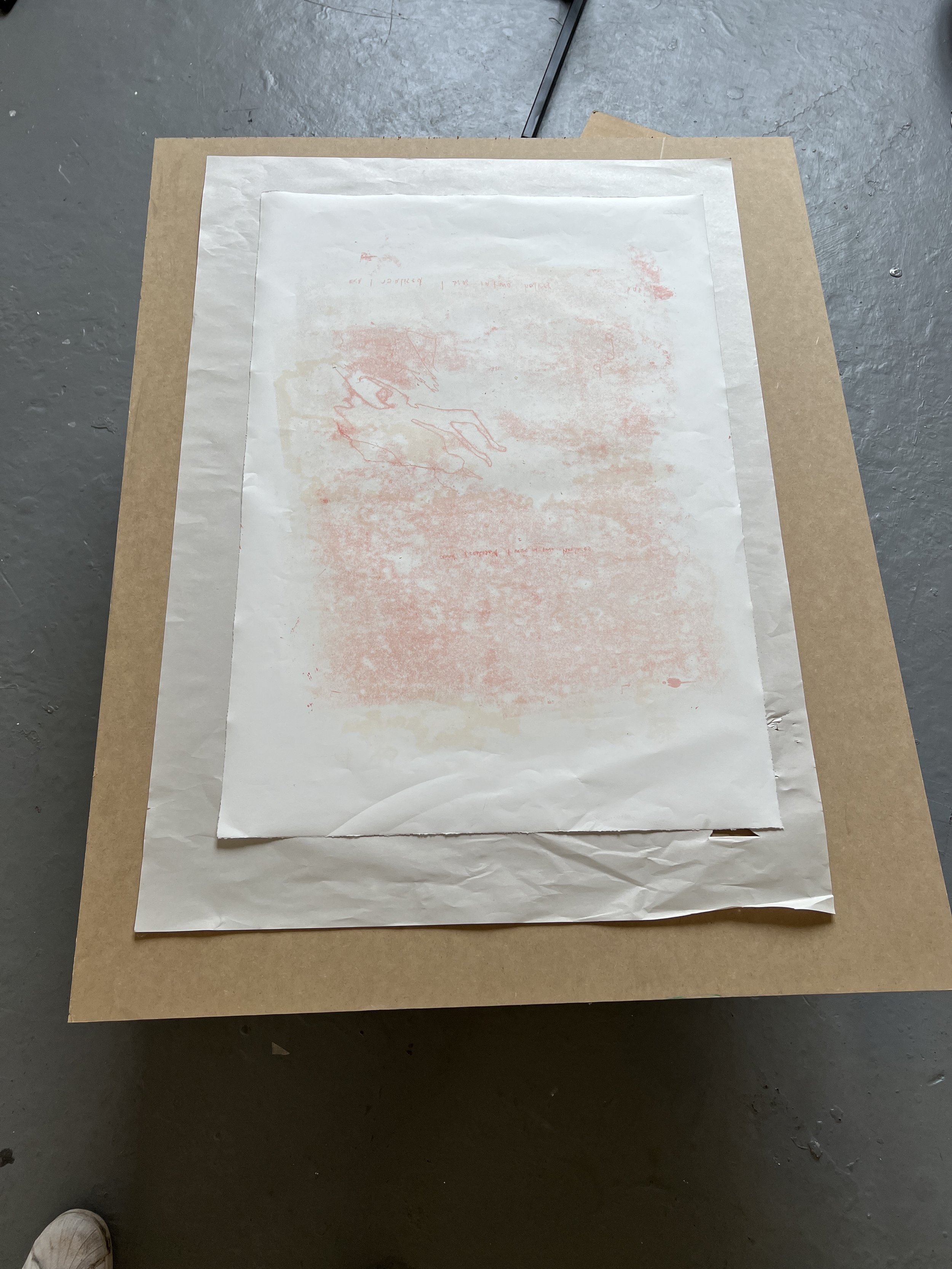

ghost print of previous plate - the plate is run through the press a second time, without re-inking

two colour plate - magenta and yellow

ghost print of previous plate

Digital separation

- photopolymer film on steel plate

- screen-printing

I used photoshop to produce 3 images for both processes and exposed them to plate and screen in the usual way – with the photopolymer plates, I used an aquatint screen to introduce a stochastic dot, rather than getting the image films custom-made with the dot. In both cases I made the mistake of forgetting to slightly expand the edges of the information within each image, to ensure that they overlap and there are no white outlines in the resulting prints. Other than this, the process was straightforward and effective. I have not had time to really test the colour palettes and it will be important for me to remember that there is not blending or overlaying of colours in this approach, so it will be important to have the colour choices absolutely right.

reference image - Rawthey Weir

digital separation by tones: mid tones

shadows

highlights

second plate of a multi-plate print

first proof: some registration issues and crazy colours! using what was left over from the hydro-coat plates

screen after washing out - i had applied the light sensitive emulsion too thickly

cleaner version of the screen on the bed

first layer in pink

second layer in yellow

yellow highlights, pink midtones, red shadow

red highlights, yellow midtones, pink shadow

Etching: hard and soft ground

- hard ground traces

Copper plates that I had prepared with hard ground came with me during the summer on walks in the Yorkshire Dales.

- soft ground traces

I had gathered and dried some wildflowers over the summer and wanted to test making impressions in soft ground, partly because I wanted to try managing the pressure on the press myself, thinking about post-MA and needing to be able to function in a print workshop without technicians doing some of these key things for me. Brian Hodgson wanted to try a new, less toxic form of soft ground, so we did some experimentation with different approaches – with at least one successful outcome.

traces left by footsteps in hard ground

indexical marks of steps taken

plate and the ground that created the marks on it

traces in White Rigg Beck

on the rocks by Cautley Beck

plate meets rock and boot

first proof of Winder to White Rigg Beck

First proof of the Cautley plates

in colour, in case my inking was responsible for the faintness of the images

multi-plate printing the Cautley plates

registration issues

re-etching with an aquatint to try to get more contrast in the prints; also using BIG ground

aquatint timings from the workshop

plates after etching

trying to ensure I get the order right when printing

this one had the lightest traces, so I etched for longer

first proof after aquatint

multi-plate print

coating copper with BIG ground to make soft ground impressions

Brian doing all the work

testing

etched plate

first proof

success: with the silk screen fabric method

Etching: screen etch resist

I wanted to revisit the viscosity print process - I had a feeling that the images of water might lend themselves to it. There is always an issue for me with this approach that, traditionally, you would use a negative image so that what is printed on to the plate in Rhinds varnish is the lighter parts of the image, those that you don’t want etched. but I often want the colour to be in those lighter parts of the image, which means they need to be etched so that the plate will hold ink there. So I did a positive and a negative of the first image so I could compare and contrast; with a negative of the rain on the River Rawthey. I have etched these all at least twice now and they are improving, but the variation in depth is still not sufficient to get a good 3 colour print.

reference image - Tschingelbach

reference image - River Rawthey

steel plate screen-printed with a negative image in Rhinds varnish

same image printed as a positive

only the exposed steel will etch, the black areas are protected from the acid

Rawthey plate after the first etch

negative plate after the first etch

first proof of the positive plate

re-etching using BIG ground and Rhinds varnish to limit deeper etching to a few key areas

first proof print

first proof of the negative plate

phthalo green, turquoise lake and vermillion

same plate with an additional relief roll of vermilion - on kozo paper

a second print , from ink passing through the very thin kozo paper and on to the soaked Fabriano paper

on hosho paper with a further relief roll

resulting virtually blind emboss on Fabriano paper

just two colours - turquoise lake and vermilion - because I didn't think there was enought variation in etching depth for three colours to work

ghost print on kozo

relief rolled with magenta

Relief Printing

I wanted to etch at least one new, large-scale image and took advantage of our early return to laser cut two water-based images at nearly 600x800mm. I wanted to use these to make more impressions in porcelain but wanted to avoid the stain from the plywood that had affected previous versions (some of the colour had burned off in the kiln, but not all of it). I tested a Galleria matt varnish against Kremer Primal using the Beevers press to make blind embosses. The Kremer varnish was much more effective at blocking the wood stain, so I coated my new, large-scale plates with this. It does have the effect of dulling slightly the edges of the etch, so porcelain impressions don’t come out quite so clean and sharp, but the porcelain is much easier to pull away from the plate. It provides a good protection for the plate while printing too - white spirit doesn’t seem to affect it and it keeps any natural colour from the wood off the prints: this would normally happen with use and several coats of ink on the plywood, but this speeds up the process. I continued to sandwich soaked canaletto paper between the print paper and blankets - this is a more uniform way of dampening fine Japanese papers which have a tendency to curl when damp and can move as the press is being prepared with even the lightest breeze.

colour ingredients

mixing ink

sponge and water for soaking paper

first print of new laser-etched woodcut

second print, on hosho paper

kozo print from the front

print on kozo paper, from behind

smaller plate printed onto hosho

kozo paper lends a kind of luminosity to this shade of ink

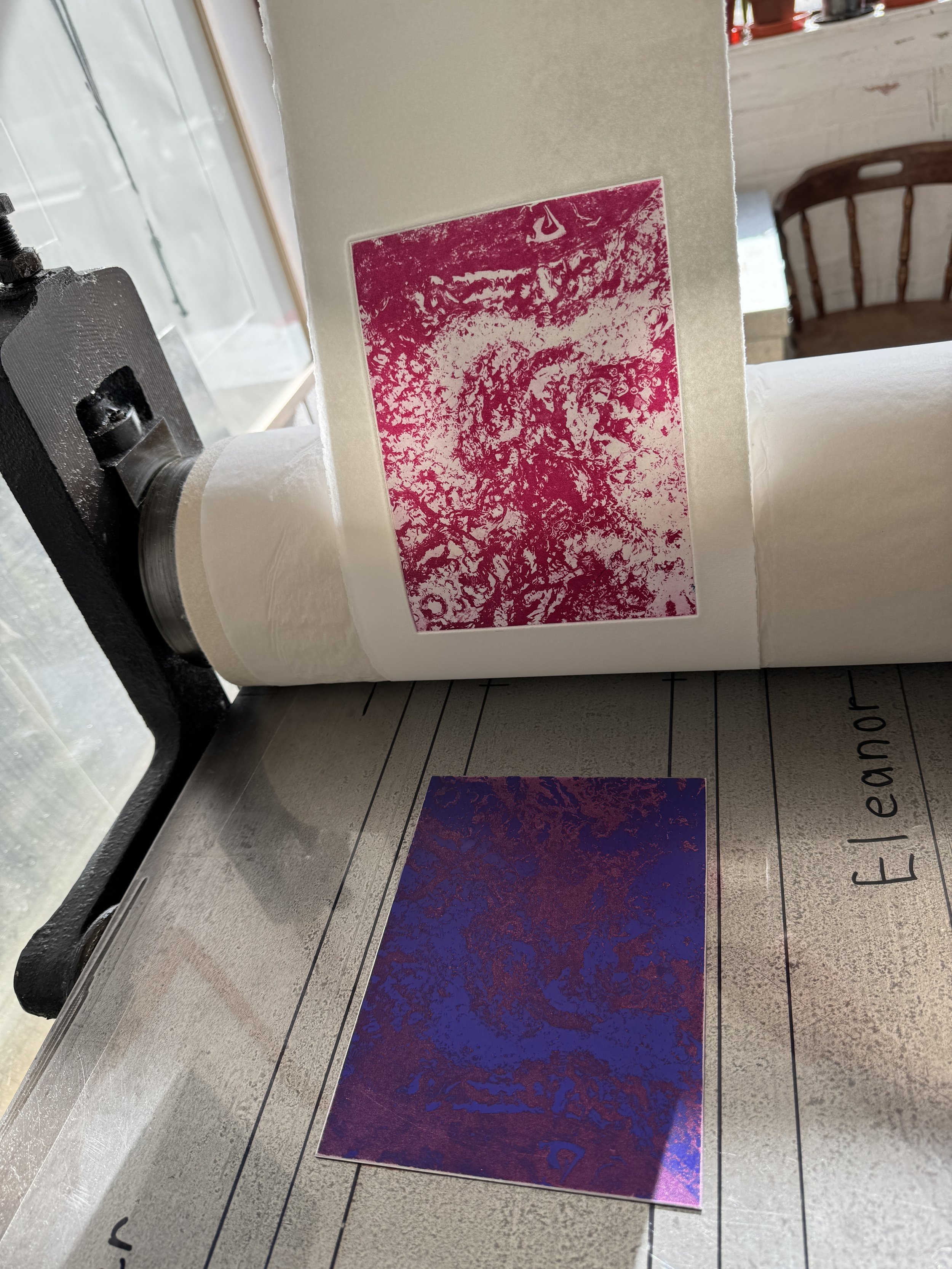

testing in pink in preparation for collaboration with Joy - on hosho

on kozo

on Zerkall

over printing Joy's monoprints

detail of collaborative print

more detail

Photography

- liquid light

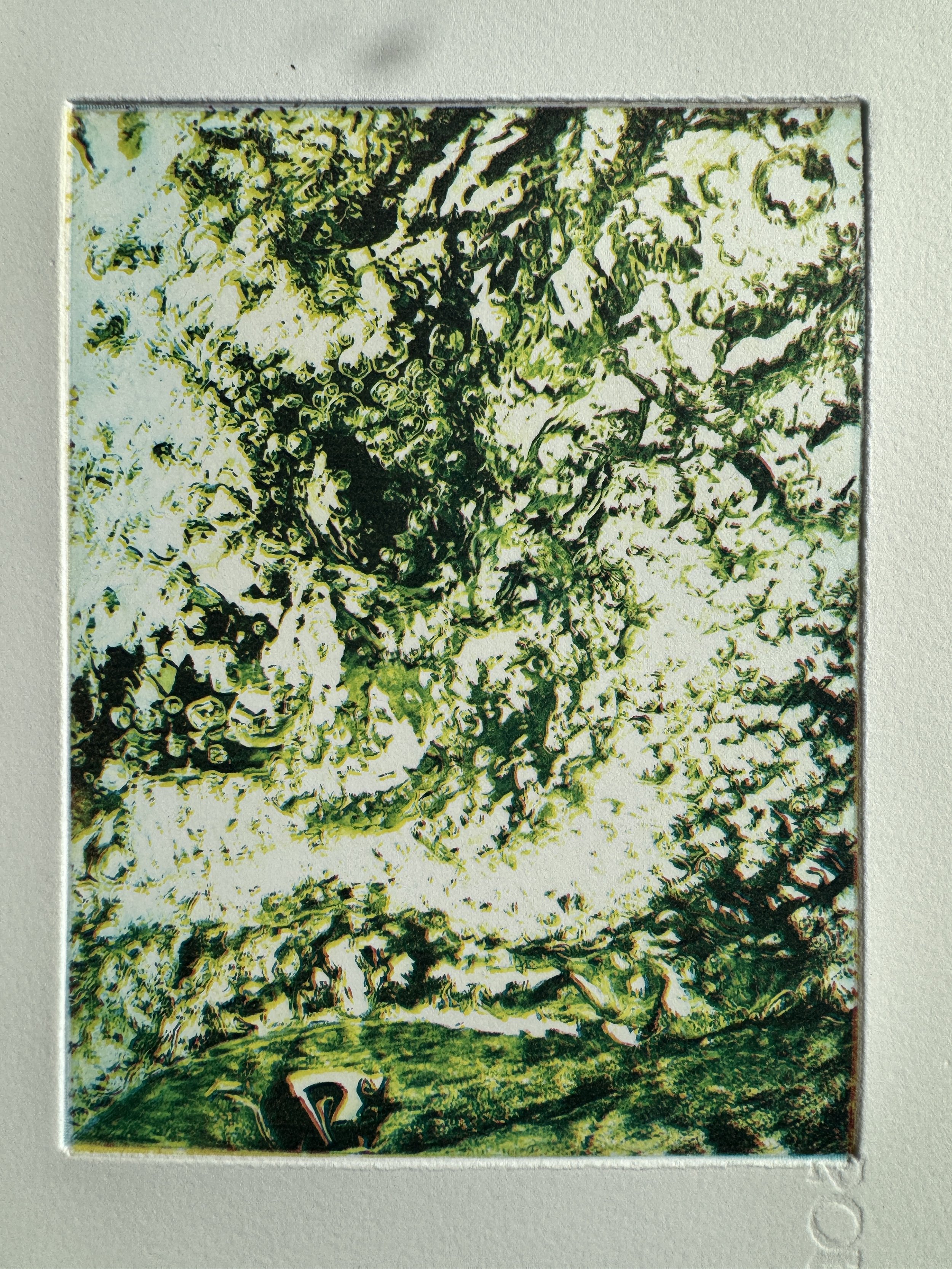

I had been keen for a while to try this form of photographic development which involves applying a photographic emulsion to a surface and developing an image in it. Hayde Sacerdote talked me through the process and set me up and I had read the book ‘Silver Gelatin’ in preparation. I had prepared some of the porcelain tiles with substrates of pva or acrylic varnish as the book suggested this might be needed with porcelain. In fact, the substrates just lifted off in the developer and I then found the (unglazed) porcelain is in fact an excellent surface for the emulsion. I had a second go without Hayde’s support, which did not turn out so well – I think due to my inexperience in photo development, probably also applying the emulsion too thickly, and perhaps not drying it sufficiently before exposing and developing. Nonetheless, I was pleased with the results, suggesting the fragility and fallibility of memory – and I was delighted to have been able to make some use of the large numbers of my dad’s photographs that I hadn’t wanted to throw away after his death.

the first efforts using photo-emulsion

I love how the surface disrupts the images in places and in others allows incredible detail and clarity

just out of the wash - in fact I hadn't left it in for long enough and it started to go a little yellow

too much emulsion, but I wanted to see what happened if exposed to light without an image

test strip for the first image I attempted on my own

Not managing anything like the same level of clarity, but I rather liked this one anyway

slightly clearer image of a tree